My Magical Marion Musical Tour

In The Beginning…

I was born in 1952 in the old hospital, across the street from the cemetery, which then became the police station (operative joke for much of my life = “I was born in jail…”) - I don’t know what it is today, some sort of business complex, I imagine.

Music was in my life from the get-go, certainly in school, as this was the age when classroom teachers had to play piano, and at least once a week the instrument would be rolled into the room, Mrs. Whosit would sit down on the bench, and accompany us on the likes of “Eric Canal”.

I grew up with my parents’ limited collection of 45s and LPs. What was unusual about their 45s (and I presume this was true of 45s from the 50s) was that most contained two songs per side. I remember very little about the music on those 45s and LPs, other than 1) a handful of records by the vanilla-but-nonetheless-seminal folk group The Kingston Trio, 2) a 45 by wild man rock 'n' roller Jerry Lee Lewis (which to prompt purchase by my parents must have been one of his tamer recordings), whom I confusedly thought was the comic Jerry Lewis, and 3) a barbershop quartet LP that, I believe, was bright yellow vinyl. None of the music made a notable impression upon me - well, I was taken by the yellow vinyl…

“Uh-Vun Anna Two”…”Promenade Left”…”Really Big Shew”

Much more memorable, though, was the music viewed on television. I grew up under the assumption that I would play an instrument (that was what upper middle class kids did; my mother had been forced by her parents to study the piano and play in recitals until her 18th birthday, when she abruptly quit and refused to play again [and, unfortunately, didn’t force any of her children to learn - indeed, I never did, despite numerous attempts, beyond a crippled “arranger’s piano”], while my father played the saxophone and ukulele, again more in his youth and young adulthood), and when time came to choose - 5th grade, for beginning band lessons - I used the television as my menu.

I settled on the trumpet as my school instrument because of the Lawrence Welk Show, and for Christmas that year I asked for a guitar, due to my regular viewing of a local central Ohio country-and-western (and square-dancing) program called “Midwestern Hayride” (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), which featured a left-handed guitarist playing a Gibson ES (in the end, the more memorable influence). Enter the $19.95 Silvertone from Sears…

And so I was positioned, metaphorically speaking, trumpet in one hand and guitar in the other, when I, eleven years old, met The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show the Sunday evening of February 9, 1964.

And so I was positioned, metaphorically speaking, trumpet in one hand and guitar in the other, when I, eleven years old, met The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show the Sunday evening of February 9, 1964.

Ed Sullivan (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), was a New York entertainment columnist who hosted what could best be called a variety show, with all sorts of different acts - comedy, music, dance, animal acts, et cetera et alia. The films Bye Bye Birdie and That Thing You Do - the latter's Hollywood Cavalcade is modeled after Sullivan's and other variety shows of the era - give a fair approximation of the weird juxtaposition of mainstream entertainment and the nascent rock 'n' rollers who appealed to America's youth. An interesting story on NPR's This American Life highlighted a comedy duo whose big break of appearing on the Sullivan show unfortunately coincided with The Fab Four’s first appearance, and how the latter overshadowed all other acts on the show that night. For my generation, The Ed Sullivan Show was our first exposure to the rock groups of the 60s, beginning with The Beatles that February night.

My life changed forever. As I sat on the floor in front of the television, with my parents in their matching armchairs behind me, music spoke directly to me for the very first time, in a way that Lawrence Welk and “Midwestern Hayride” had emphatically not. The sound, the energy, the enthusiasm - this was the greatest thing I'd ever heard and, not insignificantly, marked the inauspicious beginnings of a stark generational distance from my parents, who laughed at and mocked both the rocking music and the shaggy look of the band.

I scraped together whatever money I could and bought their first album, Meet The Beatles. Back then, LPs were available in monophonic (the same sound emanating from both speakers) or stereophonic (some instruments on one side, some on the other, and some mysteriously hovering right in the middle) formats. (Remember? - “Hello, boomer…”) Mono was $1.98 and stereo was $2.98, and two dollars was (barely) all I could scrounge. No matter to me, mono or stereo - the music was simply glorious and belonged solely and completely to me and my peers, no parents allowed. Today that album is framed in my basement.

That first, seminal mono album marked the beginning of my record collection. Shortly thereafter I joined the Columbia Record Club (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), wherein one famously received ten free albums with a purchase of one record and a commitment to buy x-amount moe (three? five? ten? I can't recall). I do remember a Sonny and Cher album and Simon and Garfunkel's Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme being in that initial acquisition.

Guitar Baby Steps

So, there I was, developing my first callouses learning to play “Red River Valley”, and after a few lessons with my trumpet teacher Bob Paxton’s son Larry (now a first call bassist in Nashville), they left town and I started up with Jerry Gibson, who taught me barre chords (Herman’s Hermits’ “I’m Henry The VIII, I Am” - remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), and helped me learn how to figure out the chords of a song from the recording. (Well, to be honest, he figured ’em out and showed ‘em to me, but I have to believe some of the process transferred over.) I also remember Ted Kohler teaching me the 9th chord formation in the Marion Country Club life guard office.

In one of the Eber Baker Junior High School talent shows, probably 8th grade, drummer Pete Robinson (who moved from Marion after 9th grade but still plays today and is intending to participate in Harding’s 50 + 1 reunion concert next August), had an instrumental combo that, I’m guessing, played something by Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), and thus Jim Burton, Randy Longacre, and I were inspired to start a band, first called “The Crumbled Cookies” (ugh), then “The Strangers” (we didn’t know about Merle Haggard’s backing band at the time).

We always, of course, struggled to find a bass player - I seem to recall that Tim Conley played with us for a little bit, but there’s a photo of us playing at the country club with only the trio, a gig that ended with the manager tossing me in the pool - My playing? My singing? The red turtleneck that color-coordinated with my single cutaway Harmony hollow body guitar? I will, alas!, never know…but look at that barre chord, willya? - thanks, Jerry!.

We did perform Paul Revere and The Raiders “Kicks” in the 9th grade talent show, and I remember struggling unsuccessfully to master the guitar solo (probably George’s, maybe Paul’s?) in The Beatles hit “I’m Down”, but nevertheless playing the tune at a Baker dance. I recall an equally unsuccessful wrestle with the guitar solo in Dino, Desi, & Billy’s “I’m A Fool” (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”) - at this point, I could figure out the chords (thanks, Jerry!) but solos weren’t as accessible, at least not to my teenage ears.

My last Strangers memory is playing a basement concert for Jim’s older sister Frannie and her friends. I stuffed a handkerchief under the strings to get that muted effect on “Mrs Brown, You’ve Got A Lovely Daughter” (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), and afterward having a band confab in which we decided that as our vocal numbers didn’t seem to go over as well as our instrumentals (audience giggling may have been involved, but that mightn’t have had anything to do with our singing abilities), we’d model ourselves after The Ventures from then on out.

And then…nothing. The Strangers didn’t carry on into Harding, and I’ve no idea why. On the other hand, the folk group I started in 9th grade with Keith Miller and Joyce Browning, The Village Voices (still a great name, I think), continued into and through high school, where we joined the Starduster Revue and gigged around the city - orchestra and choir teacher George Lane would often recommend us if a civic group phoned Harding looking for cheap (i.e., free) entertainment. We recently reunited online after 50 years (and our reunion video can be seen at the end of this tome).

“I’ll Play Bass…”

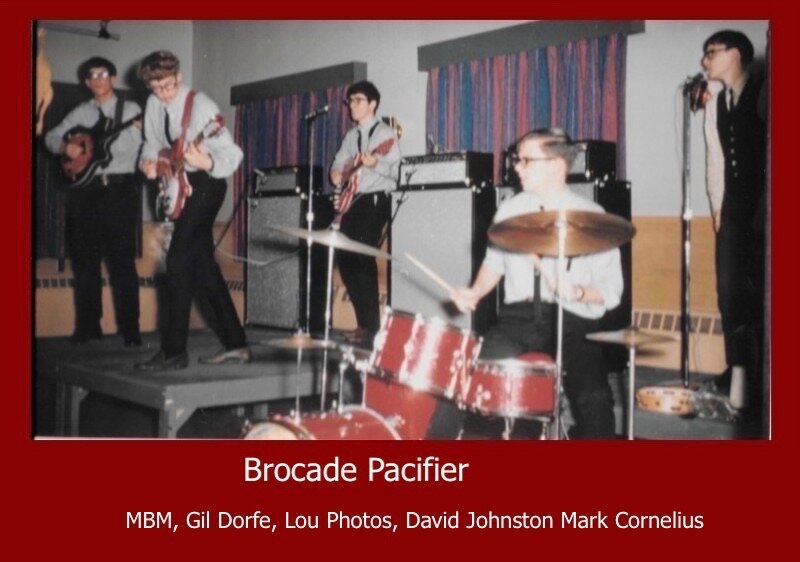

I had continued with trumpet, and so, one Friday night the fall of my sophomore year (and, as Baker back then was 7th-8th-9th grade, my first year at Harding), I was sitting in my uniform with the rest of the marching band waiting to trek down to the stadium for the game, when the trumpeter beside me, Mark Cornelius, said, “We need a bass player for my band,” and I replied, “I’ll play bass for you.” Mind you, I’d never played bass before, but operated with the usual guitarist misconception that, with two less strings, how hard could it be? I somehow borrowed Ken Eddington’s bass, and, the next day, met, rehearsed with, and became a member of The Brocade Pacifier, joining Mark, Lou Photos, Gil Dorfe, and David Johnston. Lou basically told me what to play (lucky me…thanks, Lou!), and the first song we worked on was The Doors “People Are Strange” (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”).

The Brocade Pacifier (Gil’s name, which, along with the still operating record emporia The Electric Fetus in Minneapolis and Magnolia Thunderpussy in Columbus, perfectly encapsulates the 60s state of mind) played all over the place - school dances, battles of the bands, Swinger (both at the YMCA and Kennedy Hall), Job’s Daughters soirees - we got paid $60 for those last gigs, a whopping $12 a man. Gil was an excellent artist, and painted the drum head and all our instruments with groovy day-glo colors (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”).

Lou Photos’ guitar, designed by Gil Dorfe.

We premiered that look at a one-on-one-audience-votes battle with John Cornelius’s “Destiny’s Children” - we were in darkness, David counted out four, and as we lit into the intro for The Rascals’ “Love Is A Beautiful Thing”, Gil stepped on the switch for the black light, and, well, “Destiny’s Children” didn’t have a chance. We also had an Echoplex and a strobe light (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”) - my goodness, those were the days!

During the band’s run, I switched from using a plectrum to fingerpicking (the song was The Stones “Jumping Jack Flash”), and remember playing The Doors “Hello, I Love You” on a flatbed truck for a 4th of July parade. We were fairly eclectic, playing everything from The Who’s “Whiskey Man” (me on French horn) to Paul Mariat’s “Love Is Blue” (Mark on trumpet) to (in addition to those aforementioned) The Beatles, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Motown, The Union Gap, Little Anthony And The Imperials, Cream, and many, many more.

The Brocade Pacifier lasted until the end of 1969, when, shortly after Jack Scott joined the band (last song on which we worked - The Who’s “I Can See For Miles”), Mark and Lou (and Jack) abandoned the rest of us to work with Rod Mitton and Dave Brammell. Gil, David, and I brought in Micki Oh-my-gosh-I-can’t-remember-her-last-name on vocals (Grimm! Finally came to me - Micki Grimm), did a bunch of Jefferson Airplane, and burnt out in short order.

Jazz

At the same time, I was educating myself in jazz, an interest the development of which I am singularly proud. Rock, folk, country, soul, musicals, even blues and rhythm & blues (those last two mostly due to the British rock musicians that I liked so much talking them up) - all these types of music were part of the formative sonic stew in which I swam as I came of age in Marion. (And I later taught myself about classical music - other than Bach and Stravinsky, with whom I was somehow familiar, strange bedfellows though they were - from the necessity that I teach the subject.)

But jazz was different. I discovered the style on my own - the music certainly wasn't on the radio or television in the 50s and 60s, at least not on the radio or t.v. listened to or watched in the Milner household, and I nurtured and developed the interest jazz sparked in me.

The first jazz album I ever purchased was New Mann At Newport by flutist Herbie Mann, a cutout LP I found as an adolescent in the racks at Woolworth's (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”). What about that particular record drew my attention? The photo? The flute? The word "jazz"? The reduced price? I certainly knew none of the songs at that time. I see in the liner notes that the music was recorded in July 1966; therefore it would have taken about a year for the album to be released and be in circulation long enough to become a cutout, so probably summer 1967 was the earliest I could have made my purchase.

I would have been 14-going-on-15 at the time and enjoying the vacation between my freshman (at Baker) and sophomore years (moving to Harding). That was the summer I went to music camp and heard The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band for the first time. I knew absolutely nil about jazz, and nothing in any of this can explain why I bought a Herbie Mann album in Woolworth's, but I credit complete serendipity that I actually found an excellent introductory jazz album.

So that was the start. In the fall I joined The Stardusters, Harding High School's jazz/big band, as a trumpeter, and found myself in with a group of people who had at least a modicum of interest in jazz. I also was playing guitar, but there was no guitar part in the ‘Dusters at that time, and trumpet was my "band" instrument. I played the third part - pretty easy - my sophomore year, but junior year I had become musically uncomfortable in band and orchestra - I found myself in the unenviable position of being simultaneously the best trumpeter in the school, and a terrible trumpeter. (Some of them, better than me, had quit, and other, more accomplished brass players were drum and bugle corps members, who had a mutually less-than-amiable relationship with the Harding music department.)

So I was the lead trumpeter in Stardusters, a position I was in no way, shape, or form able to fill…that was an uncomfortable stint. The following summer I taught myself to read bass clef and senior year switched to acoustic and electric bass, the former I just picked up while the latter I had been playing for less than two years in the Pacifier. In addition to that swap in ‘Dusters, I switched to French horn in orchestra, but continued my unhappy relationship with trumpet in band.

What I learned later is that I simply was not genetically gifted with a trumpet embouchure - I could play French horn, with its smaller bore mouthpiece, for hours without a hitch, and, later, similarly, baritone and tuba, with their larger mouthpieces, but trumpet, right in the middle, had been a profoundly bad choice for me - damn Lawrence Welk… I was far more adept playing string and electric bass than trumpet, and I quit the latter altogether a few years later. (Although, handed a trumpet today, I can still squawk out, with appalling tone, the Harding fight song.)

After that, things started moving quickly, with two early events that I would consider significant: 1) at some point I bought a book titled The Big Bands by noted jazz critic George Simon which had an accompanying three-record set, with which I gave myself the beginnings of my historical education, and 2) I ended up subscribing to DownBeat, which was the jazz magazine and my main source of information about jazz past and present until I cancelled my subscription in the wake of a critic's snarky pan of John Mayall's Turning Point album, which I loved/love.

One of my favorite memories of all time = end of senior year, the Panorama concert at which all the Harding groups performed, and Ned Hall and I, armed with two guitars, performed Fran Landesman’s and Tommy Wolf’s “Spring Can Really Hang You Up The Most”, which we had learned from the Helen Merrill/Dick Katz album A Shade Of Difference, purchased by me due to a four-star review in DownBeat. Afterwards, uber-hip trombonist Marion Burton came up to us and said, “Only musicians know that song…” Ned and I were over the moon - certainly one of the greatest compliments I ever received.

I was an emphatic jazz aficionado in high school (a rarity then as now), buying, for example, albums by Miles Davis’s classic quintet (Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams) as they were released, so I have been into the music for over 50 years, almost as long as my love affair with the popular styles listed in the second sentence of the fifth paragraph above.

Progressions…And Buddy

I graduated from taking guitar lessons at Erickson’s to teaching there myself - favorite story from then = a note saying “Please tell Mack Milford I won’t be coming today”, which provided me with a nom de modeste, utilized when I thought I had too many credits in a project, that I employ to this day. And, of course, I was a regular in the music store’s back room, hanging with both the older musicians who came before me and the younger underclassmen on my heels.

Sometime during my junior year, after Ned moved to town and he and I had become fast friends, we joined (wife of our band director) Phyl Miller in a trio and played most weekends at The Keg and Vine. That band was a mutual-admiration-learning society, as Phyllis introduced us to lots of jazz, and we supported her journey into rock and pop. We had that gig most weekends until we graduated.

In 1968, I started writing music, and my first chart was an original called “Three’s A Crowd” for Stardusters. I also started writing charts for the Al Wayne Orchestra, a sextet of sax/trombone/trumpet/piano/bass/drums. With virtually no training, I was finding my way as a musician/composer/arranger.

Between junior and senior year, Ned went to a Berklee College of Music summer session, and John MacPherson and I went east to visit 1) Ned in Boston, 2) the Isaly family (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”) in Princeton, 3) New York City, and 4) the Newport Jazz festival.

Here’re favorite stories from that last one = the outstanding drummer and bandleader Buddy Rich was, by virtually all accounts, a prick. He was infamous for getting back on the band bus after a gig and viciously berating his musicians for hours on end with profanity-drenched tirades about every single little thing that had gone wrong. After a while, some of the musicians started surreptitiously taping these rants, and the recordings were passed around for years - you can hear some on YouTube - search "Buddy Rich bus tapes“.

David Johnston and I saw the band in Columbus, Ohio once, and David found himself standing beside Rich at a urinal. David offered some compliments (he loved Buddy), but got only guttural, noncommittal, ungracious grunts in response. When MacPherson and I saw the band at the Newport Jazz Festival, they brought down the house. Everybody was screaming for an encore, and Rich said, "Do you want to hear 'West Side Story Medley' or 'Channel 1 Suite'"? We all screamed, "'West Side Story Medley!!!" "Okay", Mr Wonderful said with a smirk, "we'll play 'Channel 1 Suite'". Quintessential Rich.

Finally, can’t resist telling this joke: the day after Buddy Rich died, his home phone rang and his widow answered. "Could I speak to Buddy?", asks a voice. "No, that's not possible", she said, "he died yesterday." "Oh, okay," says the voice, and hangs up. The next day the phone rings. "Could I speak to Buddy?", inquires the same voice. She's not sure what's going on, but replies, "No, he died." The caller hangs up. The next day, same thing. On the fourth day, when he calls, the widow says, "Look, what's going on? I've told you three days in a row and I'm telling you now, he died!" "I know", says the caller, "I just like to hear you say it."

Boston, Eventually

When I graduated Harding, I was too afraid and insecure to go to Berklee, so I spent a year at Bethany College in West Virginia, where I had my very first theory-harmony-ear-training classes, which started filling in the blanks in my musical self-education, and I played in jazz bands with various faculty members and students. However, I managed to muster the confidence to apply to Berklee for the following year. I was accepted, and that summer I assembled, wrote the music, and produced a concert for the first Mark Milner All-Star Big Band, which I only mention to explain the exponential growth I experienced at Berklee.

For that first All-Star band, all of my arrangements were transcriptions of my limited piano playing, so that the three horn sections - trumpets, saxophones, and trombones - were arranged in close harmony, what the four or five fingers finding the parts on the keyboard could play. At Berklee, I learned how bigger, more open voicings (which I couldn’t play on the piano) could provide bigger, more open sounds (not to mention voicing in fourths, fifths, clusters, contrary motion, line writing, et cetera et alia).

An amusing Berklee digression = the head of the arranging department was a drummer and great guy with an excessively dry wit named Ted Pease (one of his tunes, “Cornerstone”, appears as a bonus track on the CD version of the aforementioned Buddy Rich Band’s classic album Keep The Customer Satisfied), and in one of the stalls in the men’s room off the Berklee lobby was the immortal graffiti “Ted Pease here…”

At Berklee, based on placement exams, I was grouped with about 20 musicians who were too advanced to go into first semester classes but had enough holes in their knowledge that we couldn’t immediately be bumped upward. The solution? We did two years of study in one year, two semesters of work each semester. Suited me to a tee, but…I experienced major cognitive dissonance in that I had never been asked to compose or arrange on demand before, and so I panicked when my professor in Chord Studies said, “Okay, for our next class write a tune using only minor-seventh chords…”

I recycled many of my previous compositions and arrangements that first semester until I got the hang of things. I also faced the fact that I had traded my big-fish-in-a-small-pond Marion status for the reverse, especially as two of my best friends were (and remain) head and shoulders above me in ability. Still, all was mitigated by being surrounded by people with whom you could have conversations such as, whilst listening to a Blood, Sweat, and Tears album, “Wow! Isn’t that bitchin’ how they went from the C chord to the Ab7?”

I played in various bands whilst in Boston, including one for which I hitchhiked regularly down Mass Ave to the club - very different times…(remember? - “Hello, boomer…”), saw much great music (Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Randy Newman, John MacLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra), and made lasting friendships. That spring I joined a Berklee pal’s former high school horn band for several recordings and performances, which led to us unsuccessfully auditioning for Vanguard Records, and spent the summer playing in a quartet with the same pal in the Catskills.

Marion Redux, Part One

Two years of musical information in one year simply overwhelmed me, I dropped out, and, at the end of the Catskill gig, moved back to Marion. I left my parental home and into an apartment, first by myself, then with Steve Long, whom I met when I arranged the Marion Cadets 1973 show, and with whom I founded “Songbird featuring Sky King”, the latter of whom Steve recruited from the railroad. I worked at Todco Doors, wrote music, and continued to play around town, most notably with Tim Sens, Michael Kingsley, and David Johnston.

That band (we considered “Rold Gold” and “The Karmechanics” before settling on the far more prosaic “Kingsley, Sens, Milner, & Johnston”) began when Tim and Mike, cousins who’d been playing as a duo, invited David and me to join them on a gig for which they needed a rhythm section. We played anywhere we could, most often at Star Lanes. We had an eclectic repertoire to rival The Brocade Pacifier, including Cole Porter’s “Miss Otis Regrets”, Paul Simon’s “One Man’s Ceiling Is Another Man’s Floor”, and Ringo Starr’s “Oh My My”.

One day, after spending eight hours at Todco standing at one end of an industrial punch press and stacking metal bars being fed from the other side by a co-worker onto a cart, I went to my parents and announced I was ready to go back to college. I started with some classes at the branch (where I had the extreme satisfaction of using a word in an English essay - “eponymous” - that the professor did not know), and ended up traveling down to Columbus several days a week for music classes.

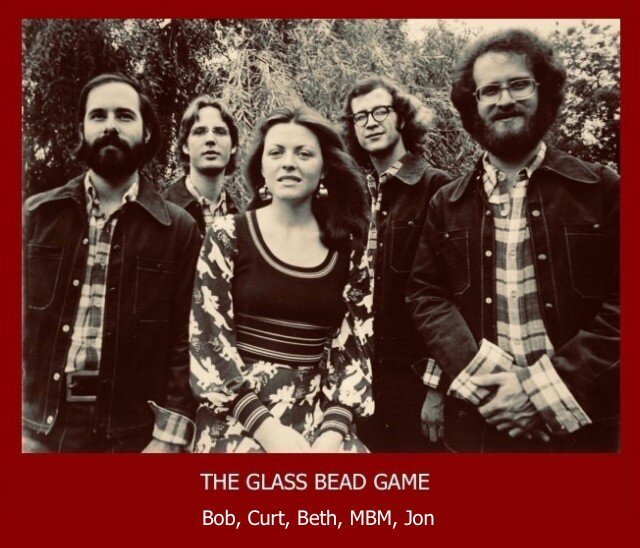

I did another All-Star Big Band, with two concerts, the first in Marion Correctional Institute (wherein vocalist Brenda Vulgamore’s rendition of “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free”, was a big hit…or, more likely, Brenda was a big hit - she probably could’ve sung the phone book…), the second in public, and in those arrangements I was able to utilize all the techniques I had soaked up like a sponge at Berklee and finally managed to assimilate. One day I woke up and said to myself, “Hold on, there, bucko, if you’re on track to finish up and get a music degree, you need to go back and do so at Berklee.” Which I did, again playing in a band - “The Glass Bead Game” (remember? - “Hello, boomer…”) - with roommates and one of our professors, going straight through four semesters - fall, winter-spring, summer, and fall again - and finishing up in December 1975 (only five years and two semesters after graduating Harding).

Marion Redux, Part Two

And then…well, I came back to Marion, which proved to be a magnet the attraction of which I simply could not break. David Johnston and I once again joined an existing group, the trio of Steve Mull and Jack and Margie Wright, first for a concert at Taft, where David taught, which was such fun we continued as “Daybreak” (that might have been the trio’s name, I can’t recall, especially as I ended up writing a song entitled “Daybreak” for us to play).

I worked selling motorcycles for Bill Sanders, got laid off when the season ended, and did one more (and last) All-Star concert, this time with a “semi-big band” of five horns and four rhythm (an instrumentation I revitalized years later in BOZO allegro) as opposed to the thirteen-and-four of previous All-Star groups. I wrote and recorded some jingles for Marion Power Shovel. I had a cable access t.v. show, where I first met and later worked with Dave Jones and Moon on their second recording. I remember co-hosting a telethon with someone from the Marion Star and CATV . Then, when Bill called the following spring to invite me back, I decided it was time to break free from Marion and move someplace whence I couldn’t come home at the drop of a hat. I’d been listening to quite a bit of Jackson Browne, so I moved to Los Angeles, where fellow ex-Marionette Mike Diehl graciously put me up until I found my own place, and my musical journey continued.

I never lived in Marion again.

Today, in my solo senior community performances, as I introduce “What A Wonderful World” and talk about the amazing atmospheric Palace Theatre and getting the autograph of Louis Armstrong therein when I was ten years old, I say, “Marion, Ohio was - and I’m only half-joking - a great place to be from. It was a wonderful town in which to be born and raised, and was the perfect place to leave behind as I moved out into the wider world.”

And, between Erickson’s Music, George Washington Elementary, Eber Baker Junior, Warren G Harding High, and all the fine musicians who crossed my path, Marion, Ohio was the ideal crucible for my musical birth, adolescence, and initial maturation.

Thanks, Marion, couldn’t’ve done it without you….

The Village Voices (MBM. Joyce Browning, and Keith Miller) reunited after 50 years to record ‘With a Little Help From my Friends’.

Biography: Mark Browning Milner

Mark Browning Miller is a pop-jazz-rock-oldtime-r&b-blues-folk-American-songbook singer-guitarist-bon vivant who takes classy and mellow songs from the 20s through the 70s and makes them his own.

He was born and raised in Marion, Ohio (a nice place to be from) which was also home to Warren G. Harding, Rod Serling, John Dean, and Gerry Mulligan, all of whom considered influences.His repertoire includes material from (ready?) Arthur Godfrey, Leonard Cohen, Bing Crosby, Taj Mahal, The Beatles, Rodgers & Hart, Dean Martin, Nick Lowe, Frank Sinatra, The Smothers Brothers, Peggy Lee, The Doors, Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Buffett, Guy Lombardo, Steely Dan, Peter, Paul & Mary, The Gershwin Brothers, Don McLean, Homer & Jethro, Little Feat, Rickie Lee Jones, The Weavers, Howlin’ Wolf, Louis Armstrong, The Grateful Dead, Irving Berlin, Joni Mitchell, Bobby Dylan, Bobby Darin, Bobby Troup, Bobby Kennedy, Abraham Lincoln, and Britney Spears. (And Groucho Marx - no kidding!).

He has entertained audiences from the gulf shores of Alabama to the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico, from the extreme southwest of Texas to the upper midwest of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and all points between and betwixt.When MBM hits the stage, anything can happen. (Sometimes the stage hits back.) Come see for yourself.